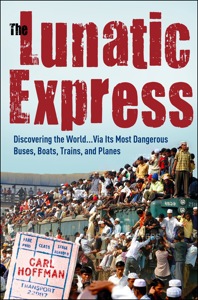

If local travel means putting oneself in the shoes of a local, then travel writer Carl Hoffman has earned status as an expert local travelite with a compelling story to tell. In his latest book, The Lunatic Express: Discovering the World via Its Most Dangerous Buses, Boats, Trains, and Planes, Hoffman relays his round-the-world jaunt aboard the rickety and rusty human conveyances that represent how the global majority transports itself. His trip utilises everything from airlines in Cuba and railways in Africa to ferries in Indonesia and long rides through the United States via Greyhound bus, logging more than 50,000 miles in total.

If local travel means putting oneself in the shoes of a local, then travel writer Carl Hoffman has earned status as an expert local travelite with a compelling story to tell. In his latest book, The Lunatic Express: Discovering the World via Its Most Dangerous Buses, Boats, Trains, and Planes, Hoffman relays his round-the-world jaunt aboard the rickety and rusty human conveyances that represent how the global majority transports itself. His trip utilises everything from airlines in Cuba and railways in Africa to ferries in Indonesia and long rides through the United States via Greyhound bus, logging more than 50,000 miles in total.

Hoffman was first attracted to local transport in all of its harrowing forms through the media’s coverage of various transportation disasters. Each chapter therefore begins with a journalistic excerpt about a fateful incident on some form of public transit. Exploring these anecdotes and researching statistics about injuries and deaths, Hoffman charts his course aboard the world’s worst transportation systems. His goal is not sensationalism or stuntman’s bravado. Rather, he aims to contrast the luxury of leisure tourism with the harsh journeys of the global poor for whom travel is simply a means of getting from point A to point B.

“I gradually began to realize,” he writes, “that the big numbers of today’s tourism industry obscured a parallel reality, excluded a whole river of people on the move. Excluded, in fact, most of the world’s travelers.”

Each segment of the trip is its own complete story, but common threads weave this journey together. Dualisms and paradoxes emerge. Hoffman begins by comparing affluent travel with public mass transit. Transportation reflects the security, comfort and regulation of affluent societies versus the danger, overcrowding and lack of controls in the less developed world. As he traverses South America on its notorious bus system, Hoffman writes “I was starting to trust the efficiency of this whole ad-hoc, unregulated system.”

One regularly recurring theme is the lack of personal space aboard the majority of mass transit. In the economics of third world transportation, “speed and maximum capacity are of the essence.” Hoffman rides matatus, the minibuses in Kenya that pull people aboard until they reach the absolute limit. He rides trains in Mumbai where the crushing pressure of the crowds becomes fatal. In an interview about the book, Hoffman reflects that the trip was a re-evaluation of what affluence means. “I’ve always sort of thought of it as objects, as things. Traveling as I did for five months, I decided that it really had nothing to do with things. It was all about space. In places like Indonesia, you’re with 3,000 people and no personal space whatsoever.” Spaces that are private and quiet and clean occur to him as a “luxury that is profound.”

Hoffman – who lives in Washington, DC – travels as the locals do but is an obvious outsider. At times the language barriers and cultural divides between himself and his fellow passengers overwhelm him. He spends pages in isolation, retreating into himself. Yet the best moments of the book are the ones where he is able to break through the cultural boundaries in order to connect with locals. On a packed ferry in Indonesia, he achieves this sort of communion: “The more I shed my American reserves, phobias, disgusts, the more they embraced me. In the weeks ahead I would accelerate what had started gradually over the miles. I would do whatever my fellow travelers and hosts did. If they drank the tap water of Mumbai and Kolkata and Bangladesh, so would I. If they bought tea from street-corner vendors, so would I. If they ate with their fingers, even if I was given utensils, I ate with my fingers. Doing so prompted an outpouring of generosity and curiosity that never ceased to amaze me. It opened the door, made people take me in. That I shared their food, their discomfort, their danger, fascinated them and validated them in a powerful way.”

This passage, like the book as a whole, beautifully illustrates the ideas of the Local Travel Movement. Hoffman continually chooses authenticity and connection with locals over the beckoning camaraderie of other foreigners. He plunges directly into the dense humanity along his route and discovers what life is like for the majority of the world’s people on the move. Turn here for encouragement as a local travelite or a reality check for one who complains on an air-conditioned flight.

sounds like a great read, thanks for sharing.

Posted by Lee Sheridan | August 31, 2010, 10:42 am